SLAC Physicists Comment on CERN Announcement Hinting at Higgs

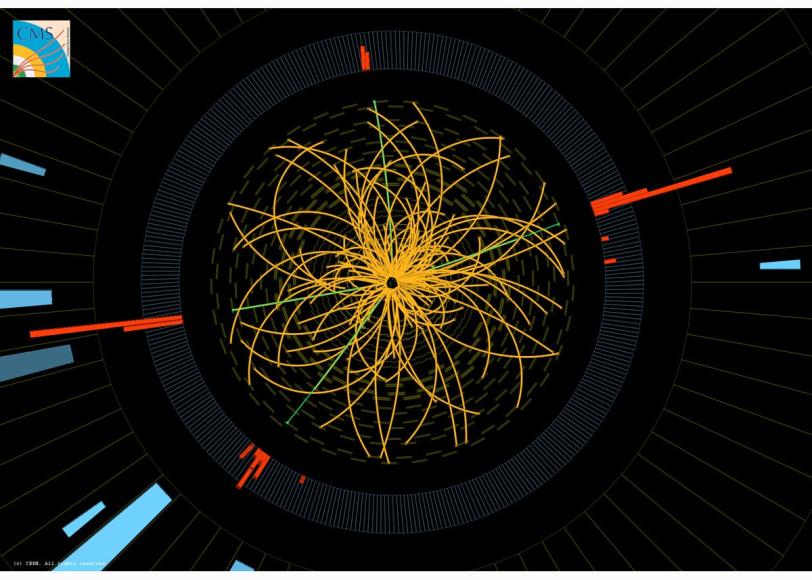

Spokespersons for CMS and ATLAS, the two biggest experiments at the Large Hadron Collider, announced yesterday that both experiments have found strong hints in their data of something that could be a low-mass Higgs boson – and added that they are well-situated to give a more definitive answer by the end of next year. But, as pointed out by SLAC physicist and ATLAS collaboration member Charlie Young, the salt shaker is still on the table.

By Lori Ann White

Spokespersons for CMS and ATLAS, the two biggest experiments at the Large Hadron Collider, announced yesterday that both experiments have found strong hints in their data of something that could be a low-mass Higgs boson – and added that they are well-situated to give a more definitive answer by the end of next year.

But, as pointed out by SLAC physicist and ATLAS collaboration member Charlie Young, the salt shaker is still on the table.

"The results are really quite interesting," he said after getting out of bed at 5 a.m. to watch the CERN webcast of a seminar where the results were announced. "But we really can't make any claims right now. The data just isn't firm enough."

There are actually a number of theoretical versions of the Higgs boson, which is thought to confer mass upon other elementary particles such as quarks and electrons. One of the prime motivations for constructing the LHC was to find the version of the Higgs that fits the Standard Model – the reigning description of physics at its most basic levels.

The Higgs boson is the only fundamental particle in that description to remain undetected, although experiments over the past decade have narrowed the mass range where it might exist. Since energy and mass are equivalent according to Einstein’s famous formula, the amount of energy required to briefly coax a Higgs particle into being corresponds to its mass; the heavier the Higgs, the more energy it takes.

According to Fabiola Gianotti, spokesperson for the ATLAS collaboration, its giant detector has gathered enough data to restrict the mass of the Higgs to between 116 and 130 GeV (billions of electronvolts), while Guido Tonelli, CMS spokesperson, said they've been able to shrink the range of Higgs hiding places to somewhere in the 115 to 127 GeV range – in striking agreement with the ATLAS results.

While those results indicate "exclusions," or statements of where the Higgs is not, both collaborations also noted "excesses," or hints of where the Higgs might be, in about the same spot – around 125 GeV.

But is it the Higgs?

"We'd like to think it's the Higgs," said Young, "But we haven't measured any of its properties yet."

SLAC theoretical physicist Lance Dixon shares Young's caution, but also considers the similar indications intriguing. "As billed, it's not discovery material, but the overlap is very interesting," he said. Dixon cautioned that he has a vested interest – a $10 bet with SLAC Director Emeritus Burton Richter – in a Higgs between 114.4 and 124.4 GeV.

Both Young and Dixon agreed with CERN Director General Rolf-Dieter Heuer, who closed the seminar with admonitions to remember that these results are preliminary and more data is required, but: "Keep in mind we're also running next year."

Stay tuned.

Related links

- SLAC seminar: Update on the search for the Higgs boson by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN (today at 12 p.m. in Panofsky Auditorium)

- Fermilab video: How do we search for the Higgs Boson?

(Photo courtesy CERN)

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.